50% Of Women Have Some Degree of Pelvic Organ Prolapse1

What Is Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP)?

Pelvic organ prolapse is the equivalent of a hernia in the tissues that support the pelvic organs. Put simply, there is weakness, damage or excessive tension in some of the tissues supporting the pelvic organs which can pull them out of their normal resting position. On this page, we will firstly review the symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse. Secondly, we will review the normal positioning of the pelvic organs and we will discuss how the position of the cervix changes during the menstrual cycle. We will explain how to check your cervical position.

We will then explore the ligaments of the uterus and how they support your pelvic organs. Thirdly, we will discuss the impact of hysterectomy on the pelvic organs. Finally, we will discuss the four main types of pelvic organ prolapse; Cystocele, Rectocele, Uterine Prolapse and Enterocele, each of which have their own page giving more information on that specific type of prolapse. If you don’t find the information you are looking for, we have a search bar at the bottom of the page that will search the site including all pages and articles. You can also jump onto our community and ask questions there. As always, speak to your doctor or another healthcare professional if you believe you may have prolapse.

Only 8% Of Women With Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) Have Symptoms Requiring Treatment2

What Are the Symptoms of Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Pelvic organ prolapse symptoms include heaviness or a dragging sensation. It can feel like there is a tampon in the vagina when there is nothing there. That is sometimes described as a “golf-ball” sensation. Stomach cramps, pain in the low-back or pelvis pain can also be a symptom, although none of these symptoms indicate that you definitely have a pelvic organ prolapse. It can also feel like you have a ball inside your vagina, or you are sitting on a ball when you sit down.

Other symptoms can include ache in the low-back, painful intercourse or a feeling of fullness in the pelvic area. Don’t ever be tempted to self diagnose, always see your pelvic floor physical therapist or gynecologist for diagnosis. These symptoms can be present without POP. Many of the symptoms are similar to those sensations you feel around menstruation. It’s important not to panic if you feel symptoms as a feeling of heaviness or a sensation of your insides coming out can be normal when on your period. If you are feeling these sensations at other times, you should make an appointment with your pelvic health physiotherapist for a check-up.

In the next section, we will learn about the normal position of pelvic organs. We will also explore how the menstrual cycle impacts the position of the cervix. This should help you to understand why there are similarities between POP symptoms and normal menstrual sensations. You will also learn about the ligaments of the uterus and their importance in supporting your pelvic organs.

What Is “Normal” Positioning of Pelvic Organs?

Before we begin, it is worth noting that although we have the same “parts” and they are in similar places, the shape, size and composition can be quite different. Even the origin and insertion of muscle and connective tissue can vary from person to person. If you stand ten women next to each other and look at the differences in body shape and size, you can begin to understand that what lies beneath the skin is also different in shape and size. These differences are hard to account for when establishing “normal”. It is also worth noting that pelvic organ prolapse is common with one in every two women having some degree of prolapse.

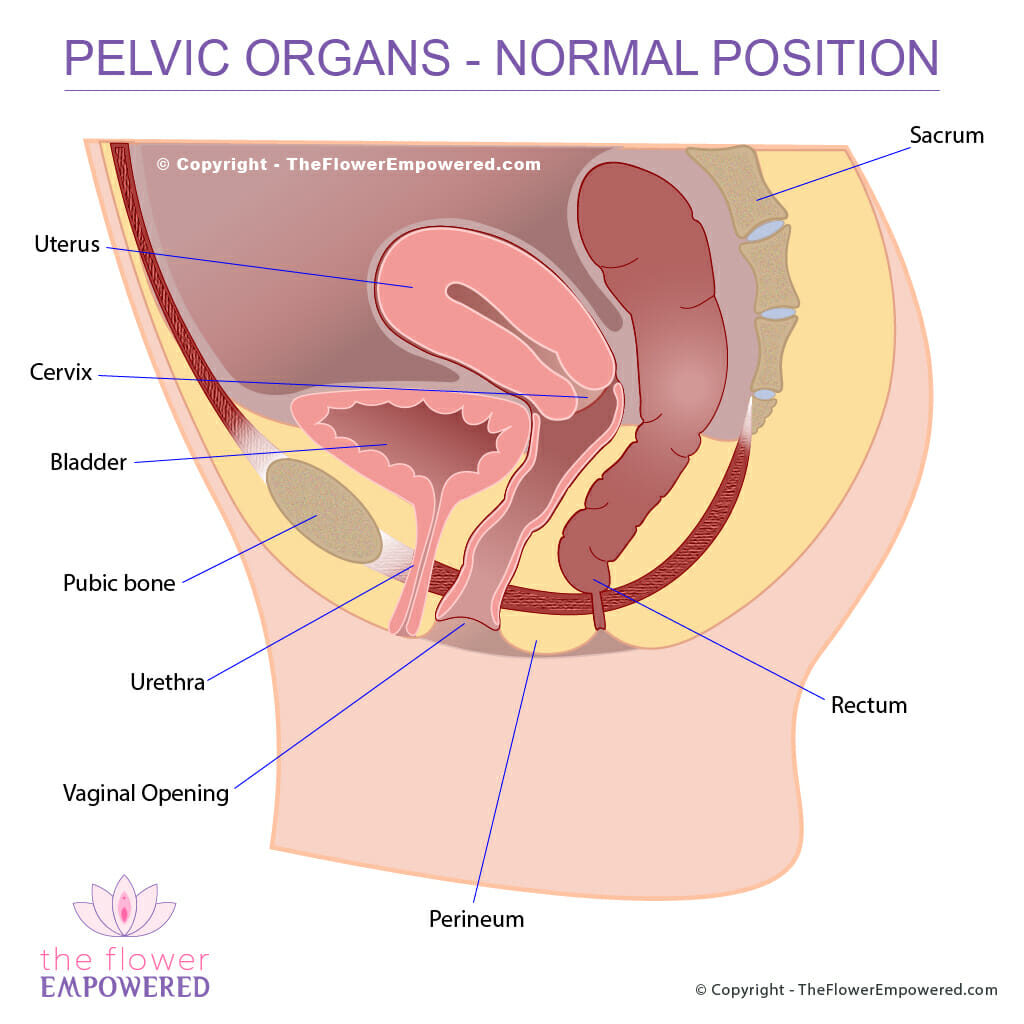

The diagram below shows the “normal” anatomical positioning of the organs within the pelvis (bladder, uterus and rectum). If you are female, you will have these organs and bones in similar positions. If you’ve had a hysterectomy, your uterus will be missing. Remember that even though we all have the same parts, they are as unique as our faces.

The Impact of Menstruation on Cervical Position

If you happen to feel your cervix is low, this is not necessarily due to POP. Before you begin to panic (which you shouldn’t do), you need to understand that your pelvic organs are not rigidly held in the exact same position at all times. The bladder and rectum are changing shape and size based on their contents (urine and poop). The uterus is changing size during the course of the monthly menstrual cycle growing significantly towards the end of the cycle. Even the position of the cervix is changing depending on where you are in your monthly cycle. There is continual movement that goes with the ebb and flow of your body’s natural rhythms. The following infographic helps to show how the position of your cervix changes throughout your cycle.

Cervix During Menstruation

If you feel like your insides are coming out during your period, this may be due to the position of your cervix during menstruation. As the month passes, there are changes to your basal body temperature, your cervical mucus, your hormone levels and the position of your cervix. You may also notice changes in your mood as your cycle progresses.

Those who practice natural family planning methods will be familiar with tracking the position of their cervix throughout the cycle, as well as tracking basal body temperature and cervical mucus. By keeping track of your body’s rhythm, you empower yourself by increasing your understanding of what “normal” is for you. You can use an app like Natural Cycles to track your basal body temperature. This app predicts your cycle and lets you know when you are fertile. You can save notes each day, giving you the opportunity to record your cervical mucus and the position of your cervix. After a few months, you should have a clear picture of your cycle. This also helps you to establish a baseline from which to identify any changes, should they occur.

The infographic image highlights these changes in a way that makes it easier to understand. The image also shows the “knuckle rule” that can help you measure the position of your cervix which we will explore in the next section.

How Do I Check the Position of My Cervix?

To check the position of your cervix (the opening to the neck of your womb), you should be standing. It might help to prop one leg up on a chair or the side of the toilet bowl. You can also make this check in the shower. Make sure you wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water before you begin.

- Relax your pelvic floor muscles

- Gently insert your middle and index fingers into your vagina.

- Feel for your cervix. The cervix feels like a bump that is soft but firm, a bit like the tip of your nose. Depending on the time in your cycle, it may feel soft or hard.

- Use the “knuckle rule” to gauge the position.

- 1st knuckle – low

- 2nd knuckle – medium

- 3rd knuckle or unable to feel it – high

My Cervix Feels Very Low, Does This Mean I Have a Prolapse?

The cervix is typically low during menstruation (one knuckle) and it can feel hard at this point. During pre and post ovulation, it rises, usually to the two knuckle mark. It rises even higher during the fertile period, where you can put your fingers in to the third knuckle and maybe still not feel it. This varies from woman to woman and you should get to know your own body using your own measuring sticks (fingers!).

If you are concerned, you should contact your doctor, pelvic floor physical therapist or gynecologist. Testing for pelvic organ prolapse is typically done by a specialist with the vulsalva movement, where you bear down as though trying to squeeze out a big poop or a baby. Some specialists will have you sit on a straddle chair or stand, although many do the test when you are lying down. It is best to have the check done during your fertile time when your uterus is at its highest. When you see your pelvic health specialist for a checkup, you can let them know at what stage in your menstrual cycle you are.

Remember that all vaginas are different. Yours may be longer or shorter than that of your friends and relatives. Get familiar with it how it looks and feels. You should now understand how your cervical position changes during your menstrual cycle. Additionally, you have learned how to check your cervical position. With that knowledge to hand, let’s delve a little deeper to understand how the pelvic organs are held in place.

On Physical Examination, Only 3% Diagnosed With Pelvic Organ Prolapse (Pop) Showed Symptoms3

The Role Of Your Pelvic Floor Muscles

Your pelvic floor muscles provide a platform beneath your pelvic organs on which they rest. A strong pelvic floor typically sits higher and provides more stability for your pelvic organs, while a weak pelvic floor sits lower and provides less stability. Hypertonicity (tight) and Hypotonicity (weak) of the pelvic floor is explained on the pelvic floor dysfunction page. Your pelvic floor does not work alone in supporting your pelvic organ’s. We like to say that the pelvic floor has “friends in high places”… that is to say that your pelvic organs are also supported by the ligaments of the uterus.

The Role of the Ligaments of the Uterus

The ligaments of the uterus are like friends to your pelvic floor, forming a network of tendinous structures that are part of your body’s network of connective tissue (fascia). Fascia is like the glue that holds your body together. It includes connective structures such as ligaments and tendons. Within your pelvis, your fascia acts like a suspension system above your pelvic floor that provides additional support for your organs.

It is important to note that fascial tissue is not uniform in its density. Your fascia is designed by your body to distribute load in what is known as biotensegrity4. Throughout your body (including your pelvis) the direction of fibres and the strength of fascial tissues will be based on your specific patterns of movement. Fascia has viscoelastic properties – viscous as in having a thick sticky consistency (like honey) and elastic meaning that it can stretch. This combination of viscosity and elasticity allows your fascia to stretch slowly then return to the original state slowly over time after the strain is removed (much like the “Stretch Armstrong” toys that you can stretch really far and then when released, they slowly return to their original shape).

Pregnancy and childbirth can stretch these fascial structures and it takes time for them to return following delivery. When you pelvic floor is weak and low, it lowers your pelvic organs causing these tissues to take the strain. If you do not strengthen your pelvic floor, they will remain in the stretched position. This would be the equivalent of pulling Stretch Armstrong’s arms but never letting go to allow him to return to his normal shape. This is why pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is so very crucial in preventing and recovering from POP.

Your connective tissues can also develop adhesions due to injury (from childbirth or surgery) or lack of movement. These adhesions are like tight bands that can prevent normal movement resulting in tugging or pulling on your pelvic organ which can contribute to POP. A 2020 study found an association between connective tissue tension and pelvic organ prolapse. One of the researchers, Anna Crowle, explains tensegrity in relation to POP on YouTube, this is worth watching. The diagram shows the main fascial ligaments that support the uterus. If you have had a hysterectomy you, you may be wondering if that can impact this support system. The answer is YES and we will discuss that next.

Does Having a Hysterectomy Cause Prolapse?

Removal of the uterus, particularly when the cervix is also removed, impacts on the stability of the ligaments of the uterus. Hysterectomies have been practiced since 1813, and many techniques have been developed to re-stabilise these support structures following uterus removal. Hysterectomy is often performed for medical reasons, however, it has become routine practice to remove the uterus during uterine prolapse repairs, even though the risk of subsequent prolapse is high (between 10 – 40%).

POP is one of the the three most common reasons for performing a hysterectomy. The uterus itself is not typically the cause of prolapse, so removal without a good medical reason should be questioned. Some studies indicate that hysterectomy could accelerate menopause by compromising the flow of blood to the ovaries. Taking all of these things into consideration, the decision to remove the uterus without a valid medical reason should not be taken lightly. If you have a hysterectomy, there is a great support forum online called Hystersisters.

I’ve Heard Prolapse Gets Worse After Menopause, Is That True?

Pelvic organ prolapse is progressive until menopause, however, after menopause, POP can either progress or regress. Regression is more common in the earlier stages of POP (Stage 1 ∼25%). One 2004 study found that “Spontaneous regression is common, especially for grade 1 prolapse”. This is another good reason to stay on top of your pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). If you can lessen the impact of your pelvic organ prolapse by optimising your pelvic health through PFMT and lifestyle changes you might increase your chances of regression after menopause.

What Causes Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Pelvic organ prolapse can be caused by hypotonic (weak) pelvic floor muscles, injury (from childbirth), previous pelvic surgery and postural imbalances (such as the loss of lumber curvature). When there is weakness or imbalance in the pelvic floor muscles and the ligaments of the uterus, this creates a path of least resistance. The location of the pelvic organ prolapse depends on where you have the most laxity. Increases in intraabdominal pressure will expose those weak points to additional stretching and pulling. For this reason, it is important to maintain balanced pelvic floor strength and to learn to manage your intraabdominal pressure. An example of management of intraabdominal pressure is safe lifting which is demonstrated in the video.

How Can You Tell if You Have Prolapse?

With POP, it is important not to self-diagnose. You should visit a pelvic floor physiotherapist or gynecologist to have a full checkup. They can confirm if you have a prolapse and they will also take measurements to assess the grade of prolapse. POP is typically measured in stages (from 0 to 4). You may have heard of the POP-Q measuring system which was introduced in the late 90’s. It is a complicated method of establishing the stage of pelvic organ prolapse and not something you would do yourself at home. You are more likely to measure based on your pelvic organ prolapse symptoms.

If you are interested knowing more on POP-Q, you can jump over to our POP-Q page. The image shown here shows the simpler Baden-Walker scale for measuring POP which shows how the stages are viewed based on the degree of pelvic organ prolapse. Note: during menstruation and even sometimes during pre and post ovulation, you may feel that you have stage 1 prolapse so it is best to measure during your fertile time when the cervix sits higher.

What Are the Different Types of Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

There are 4 main types of pelvic organ prolapse: Cystocele, Rectocele, Uterine Prolapse and Enterocele. CELE means hernia or protrusion. It is not unusual for someone to present with more than one type of POP at the same time. You can read more on the different types of pelvic organ prolapse and their treatments by clicking on the buttons below. If you don’t find what you are looking for, just use the search bar at the bottom of the page to search this site.

Treatment for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Like most symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, the treatment for Pelvic Organ Prolapse falls into one of two categories; conservative (non-surgical) and invasive (surgical). Surgical options are generally only advised for severe prolapse (grade 3 or 4). For more information on the various treatments offered in these two categories, click on the relevant button below. If you did not find what you were looking for, you can search this site using the search bar at the bottom of the page.

References

- Barber MD, Maher C. Epidemiology and outcome assessment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Nov;24(11):1783-90. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2169-9. PMID: 24142054.

- Pelvic Organ Prolapse, Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery: 7/8 2017 – Volume 23 – Issue 4 – p 218-227 doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000430

- Aboseif C, Liu P. Pelvic Organ Prolapse. [Updated 2021 Oct 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563229/

- Dischiavi SL, Wright AA, Hegedus EJ, Bleakley CM. Biotensegrity and myofascial chains: A global approach to an integrated kinetic chain. Med Hypotheses. 2018 Jan;110:90-96. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.11.008. Epub 2017 Nov 20. PMID: 29317079.